Howard Waitzkin, MD, PhD, Celia Iriart, PhD, MPH, Alfredo Estrada, MD and Silvia Lamadrid, MA

Social Medicine Then and Now: Lessons From Latin America

American Journal of Public Health October 2001, Vol 91, No. 10 | 1592-1601

Howard Waitzkin and Celia Iriart are with the Division of Community Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Celia Iriart is also with the Central Organization of Argentine Workers (Central de Trabajadores Argentinos), Buenos Aires, Argentina. Alfredo Estrada and Silvia Lamadrid are with the Group for Research and Training in Social Medicine (Grupo de Investigación y Capacitación en Medicina Social), Santiago, Chile. Silvia Lamadrid is also with the University of Chile, Santiago.

Correspondence: Requests for reprints should be sent to Celia Iriart, PhD, MPH, University of New Mexico, 2400 Tucker Ave NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131 (e-mail: iriart@unm.edu).

ABSTRACT

The accomplishments of Latin American social medicine remain little known in the English-speaking world. In Latin America, social medicine differs from public health in its definitions of populations and social institutions, its dialectic vision of “health�illness,” and its stance on causal inference.

A “golden age” occurred during the 1930s, when Salvador Allende, a pathologist and future president of Chile, played a key role. Later influences included the Cuban revolution, the failed peaceful transition to socialism in Chile, the Nicaraguan revolution, liberation theology, and empowerment strategies in education. Most of the leaders of Latin American social medicine have experienced political repression, partly because they have tried to combine theory and political practice�a combination known as “praxis.”

Theoretic debates in social medicine take their bearings from historical materialism and recent trends in European philosophy. Methodologically, differing historical, quantitative, and qualitative approaches aim to avoid perceived problems of positivism and reductionism in traditional public health and clinical methods. Key themes emphasize the effects of broad social policies on health and health care; the social determinants of illness and death; the relationships between work, reproduction, and the environment; and the impact of violence and trauma.

ALTHOUGH SOCIAL MEDICINE has become a widely respected field of research, teaching, and clinical practice in Latin America, the accomplishments of this field remain little known in the English-speaking world. This gap in knowledge derives partly from the fact that important publications remain untranslated from Spanish or Portuguese into English. In addition, the lack of impact reflects a frequently erroneous assumption that the intellectual and scientific productivity of the Third World manifests a less rigorous and relevant approach to the important questions of our age.

In this article, we describe the history of the field, depict the challenges of leadership and daily work activities, and analyze the debates, theoretic approaches, methodological techniques, and major themes emerging from Latin American social medicine. We also present Latin American perspectives on the definition of social medicine and on the perceived differences between social medicine and traditional public health. A separate article presents a critical review of work conducted at the major centers of social medicine in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, and Mexico.1 Our methods included a review of publications and unpublished literature in Spanish and Portuguese, a study of archives, and focused, in-depth interviews with leaders, health care practitioners, and lay participants in social medicine programs. (A summary of the methods can be obtained from the corresponding author or at the Web site http://hsc.unm.edu/lasm.)

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

Most Latin American accounts of social medicine’s history emphasize its origins in Europe.2,3 Such historical accounts usually cite the work of Rudolf Virchow in Germany.4 Especially through his political activism in the reform movements that culminated in the revolutions of 1848, Virchow initiated a series of influential investigations concerning the effects of social conditions on illness and mortality. Presenting pathologic observations and statistical data, he argued that the solution of these problems required fundamental social change. Virchow defined the new field of social medicine as a “social science” that focused on illness-generating social conditions.5�7

Adherents of Virchow’s vision immigrated to Latin America near the turn of the 20th century. Virchow’s followers helped establish departments of pathology in medical schools and initiated courses in social medicine. For instance, a prominent German pathologist, Max Westenhofer, who directed for many years the department of pathology at the medical school of the University of Chile, influenced a generation of students, including Salvador Allende, a medical student activist, pathologist, and future president of Chile.8

Salvador Allende and the “Golden Age” of Social Medicine in Chile

Although the roots of Chilean social medicine date back to the mid-19th century, the most sustained activities began after the nationwide strikes of 1918. During that year, saltpeter workers in the northern desert encouraged work stoppages in other industries, with the goal of improving wages, benefits, and working conditions. Luis Emilio Recabarren, a charismatic organizer among the saltpeter workers, emphasized the destructive effects of malnutrition, infectious diseases, and premature mortality. During the next 3 decades, Recabarren and his political allies agitated for economic reforms as the only viable route to improvements in patterns of illness and mortality that affected the poor. During the 1920s and 1930s, social medicine flourished in Chile, partly as a response to the demands of the labor movement.

Allende’s experiences as a physician and pathologist shaped much of his later career in politics. Acknowledging debts to Virchow and others who studied the social roots of illness in Europe, Allende set forth an explanatory model of medical problems in the context of underdevelopment. Although parallel activities in social medicine were occurring during the same period in North America and Europe,9,10 these developments do not appear to have directly influenced Allende’s work.

Writing in 1939 as minister of health for a newly elected popular front government, Allende presented his analysis of the relationships between social structure, disease, and suffering in his classic book, La Realidad Médico-Social Chilena (The Chilean Medico-Social Reality).11 This book conceptualized illness as a disturbance of the individual fostered by deprived social conditions. Breaking new ground in Latin America at the time, Allende described the “living conditions of the working classes” that generated illness. He emphasized the social conditions of underdevelopment and international dependency, as well as the effects of foreign debt and the work process. In this book, Allende focused on several specific health problems, including maternal and infant mortality, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted and other communicable diseases, emotional disturbances, and occupational illnesses. Describing issues that had not been studied previously, he analyzed illegal abortion, the responsiveness of tuberculosis to economic advances rather than innovations in treatment, housing density in the causation of infectious diseases, and differences between generic and brand-name pricing in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Ministry of Health’s proposals that concluded La Realidad Médico-Social Chilena took a unique direction by advocating social rather than medical solutions to health problems. Allende proposed income redistribution, state regulation of food and clothing supplies, a national housing program, and industrial reforms to address occupational health problems. Rather than seeing improved health care services as a means toward a more productive labor force, Allende valued the population’s health as an end in itself and advocated social changes that went far beyond the medical realm.

Allende’s analytic position in social medicine lay behind much of his political work until his death in 1973 during the military coup d’état. In addition to the work of Virchow and Westenhofer in pathology, the Civil War in Spain influenced Allende, as it did many later practitioners of social medicine in Latin America. The struggle against fascism and for a more egalitarian society in Spain during the late 1930s led to a movement for improved public health among activists in the exiled Spanish Republican community. Allende and his supporters incorporated principles from the Spanish public health movement into their efforts for change in Chile.

As an elected senator in the early 1950s, Allende introduced the legislation that created the Chilean national health service, the first national program in the Americas that guaranteed universal access to services. He linked this reform to other efforts that aimed to achieve more equitable income distribution, job security, improved housing and nutrition, and a less dominant role for multinational corporations within Chile. Similarly, as a senator during the 1960s and elected president between 1970 and 1973, Allende sought reforms in the national health service and other institutions that would have achieved structural changes throughout society. Because of his advocacy of a unified health service in the public sector, the Chilean national medical association (Colegio Médico) feared the effects of Allende’s policies on private practice and therefore frequently opposed him, especially before the coup of 1973.

Social Medicine vs Public Health Elsewhere in Latin America

Other Latin American countries did not advance as far in adopting the perspectives and activism that characterized Chile during the 1930s. Public health efforts throughout Latin America, as clarified recently by several major investigations,12�18 provided a background to which contemporary practitioners of social medicine responded. For instance, leaders of social medicine in many Latin American countries reacted critically to the Rockefeller Foundation’s public health initiatives, which emphasized the productivity of labor in enhancing the ventures of US-based multinational corporations.19�21 However, from our literature review and interviews, we conclude that the early history of social medicine in some countries proved much more influential than in others. Although substantial early public health efforts occurred in Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico, current leaders in social medicine view the influence of these attempts as less important for social medicine than those in Chile, Argentina, and Ecuador.

Both historically and currently, leaders in Latin America have distinguished social medicine from traditional public health.

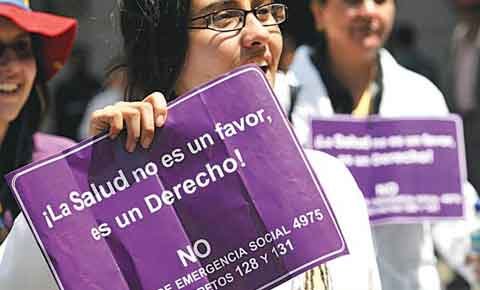

Both historically and currently, leaders in Latin America have distinguished social medicine from traditional public health. From this perspective, public health tends to define a population as a sum of individuals. Specific characteristics, such as sex, age, education, income, and race/ethnicity, permit the classification of these individuals into groups. In traditional epidemiology, rates for a population are calculated arithmetically from the characteristics of individuals who compose the population. By contrast, much work in social medicine envisions populations, as well as social institutions, as totalities whose characteristics transcend those of individuals.4 Social medicine therefore defines problems and seeks solutions with social rather than individual units of analysis. In this way, the population can be analyzed through such categories as social class, economic production, reproduction, and culture, not simply through the characteristics of individuals.22�24

Another distinction between social medicine and traditional public health concerns the static vs dynamic nature of health vs illness, as well as the effect of social context. Social medicine conceptualizes “health�illness” as a dialectic process rather than a dichotomous category. As in Eng-els’s earlier and Levins and Lewontin’s more recent interpretations of dialectic processes in biology,25,26 critical epidemiologists have studied disease pro-cesses in a contextualized model, considering the changing effects of social conditions over time. The epidemiologic profile of a society or group within a society requires a multilevel analysis of how social conditions such as economic production, reproduction, culture, marginalization, and political participation affect the dynamic process of health� illness. In this theoretic vision, multivariate models in public health (such as recent logistic regression models with disease as a dependent variable, dichotomized as either present or absent) obscure health�illness as a dialectic process.27

By contrast, in Argentina during the 1920s, a group led by Juan B. Justo tried to go beyond the public health initiatives of the time, known as “hygienic” interventions (higienismo), which emphasized infection control, improved sanitation, nutrition, and similar efforts to improve population health.28 Higienismo usually aimed to improve labor force productivity, in the interest of national development and international investment. Justo, a surgeon, became a founding leader of the Socialist Party and provided an early Spanish translation of Marx’s Capital. Like Allende, Justo called attention to the pervasive effects of social class on health services and outcomes.29 This work led to regional and national organizing efforts that sought broad social change as the basis of improved health. However, as higienismo gained dominance, Justo’s was a minority position.

Another line of work in social medicine that grew from Argentine roots was that of Ernesto (“Che”) Guevara. Guevara’s childhood asthma, as well as role models in his family, led him to enter medical school and eventually to specialize in allergic diseases. After medical school, he toured South America, Central America, and Mexico by motorcycle. Through experiences of poverty and suffering during this trip, he developed his views about the need for revolution as a prerequisite for improving health conditions.30

In his speeches and writings on “revolutionary medicine,” Guevara called for a corps of physicians and other health workers who understood the social origins of illness and the need for social change to improve health conditions.31,32 Guevara’s work profoundly influenced Latin American social medicine. One might expect that Guevara’s views developed partly from knowledge about Allende, Justo, and others who preceded him, but apparently this was not the case. Sources close to Guevara, including an uncle who served as a role model in medicine, claimed that throughout his medical training and career Guevara remained unexposed to earlier works in Latin American social medicine and that he developed his analysis linking health outcomes with social conditions largely through experiences during his motorcycle trip (Francisco Lynch Guevara, oral communication, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1995).

In Ecuador, leaders in social medicine trace their local roots back more than 150 years. During the early 19th century, the physician Eugenio Espejo linked his work as a physician to the revolutionary struggles against Spain.33 In his efforts to control epidemics, Espejo became convinced, as Virchow later would in Germany, that poverty, inadequate housing and sanitation, and insufficient nutrition fostered such outbreaks. Later, in the early 20th-century movement toward social security, Pablo Arturo Suárez’s book on “the situation of the working class” provided epidemiologic data on adverse health outcomes.34 During the 1930s, the physician Ricardo Paredes studied occupational lung diseases and accidents among Ecuadoran miners working at a US-owned mining company.35 In addition to legislation that improved working conditions, Paredes’s efforts led to a broad consciousness in Ecuador of the effects on health of “economic imperialism” by multinational corporations.

The 1960s and Later

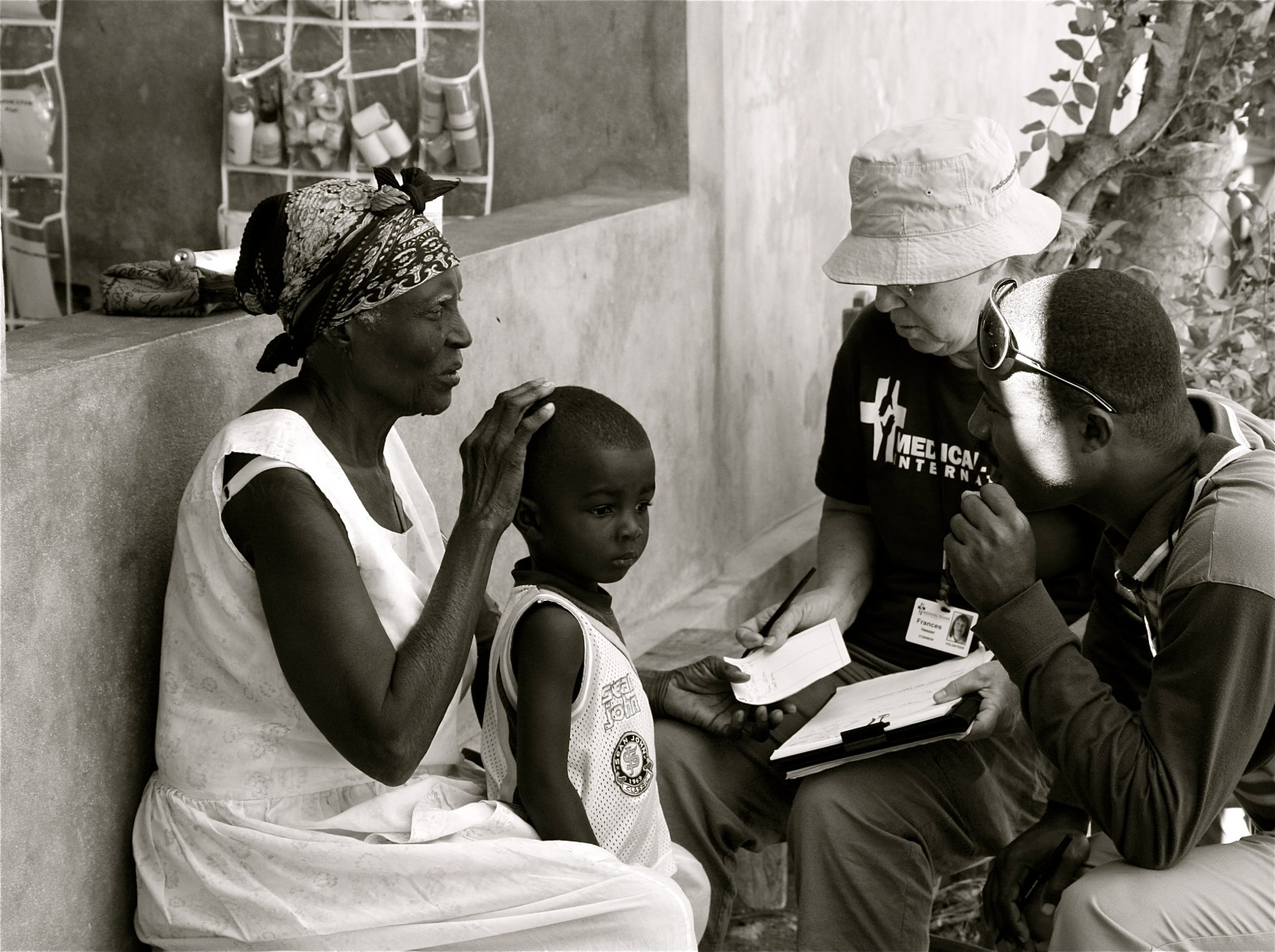

Among the changes that occurred worldwide during the 1960s, the Cuban revolution, which began in 1959, emerged as one of the most important for social medicine. Cuba’s improved public health system emerged as part of a social revolution in which accomplishments in health occurred as an integral part of broad structural changes in the society as a whole.36,37 The social changes underlying Cuba’s achievements in primary care, public health, medical education, planning and administration, and epidemiologic surveillance inspired activists and scholars in other countries.

If Cuba provided a positive model for Latin American social medicine, Chile created ambivalence. Social medicine groups took a keen interest when Allende and the Unidad Popular government achieved victory in 1970. Many people in social medicine came to Chile to work with the new government. Allende had proposed a peaceful transition to socialism through electoral rather than military means�the first such transition in history. The government moved toward a “unified” national health program, in which the contradictions of coexisting private and public sectors would be reduced. After the violent coup d’état of 1973, repression of the population and especially of health workers reached unprecedented levels of violence.38,39 The failure of the peaceful road to socialism left a mark on those throughout Latin America who pursued social medicine.

Nicaragua’s revolution of 1979 also inspired social medicine activists, although many worried about the health-related social policies of the Sandinista government. Leaders of social medicine from several countries contributed to the new Nicaraguan government’s health reforms, including extensive programs that dealt with infectious diseases and with maternal and child health.40,41 These leaders’ concerns, which were never published, focused on the contradictions of the Nicaraguan revolution, which, for instance, permitted a continuing major role for private practice, even for health professionals who worked full-time for the national health service. Government representatives argued that such policies enhancing the private sector of the economy would prevent an exodus of health professionals similar to the one that had occurred in Cuba. Owing to such contradictions, some social medicine leaders eventually reduced their support activities, especially after the Sandinistas’ electoral losses.

Liberation theology became a source of inspiration for many of social medicine’s activists.

Liberation theology became a source of inspiration for many of social medicine’s activists. Priests such as Frei Betto in Brazil advocated participation in “base communities,” which fused religious piety with struggles for social justice.42 These struggles included efforts to improve health and public health services. Certain leaders of liberation theology grew skeptical about nonviolent processes in base communities. Influenced by Camilo Torres, a priest who joined the revolutionary movement in Colombia, some social medicine activists entered armed struggle in several countries and later returned to the practice of social medicine.43

Another important influence on social medicine stemmed from the educational innovations of Paulo Freire and coworkers in Brazil. Through adult literacy campaigns, Freire encouraged people in poor communities to approach education as a process of empowerment. In the efforts that led to his classic book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed,44 Freire fostered the organization of small educational “circles,” by which local residents could link their studies to the solution of concrete problems in their communities. Activists later began to extend this approach to public health education and organizing to improve health services.45 Freire himself became more interested in applications of empowerment strategies to health.46 While Freire’s orientation also has affected public health in the United States,47,48 the impact proved even greater in Latin American social medicine.

During the 1970s, a leader emerged who profoundly affected the course of social medicine from a base in Washington, DC. Trained as a physician in Argentina and as a sociologist in Chile, Juan César García served as research coordinator within the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) from 1966 until his death in 1984. García himself produced seminal works on medical education, the social sciences in medicine, social class determinants of health outcomes, and the ideologic bases of discrimination against Latinos.49�52 Although his Marxist social philosophy manifested itself in several works published under his own name while he was working for PAHO, he also published more explicitly political articles under pseudonyms (A. Mier, unpublished observations, 1975).

García affected social medicine through the financial and socioemotional support that he provided through PAHO. With his colleague at PAHO, María Isabel Rodríguez, who was living in exile after serving as dean of the school of medicine at the University of El Salvador, García orchestrated grants, contracts, and fellowships that proved critical for social medicine groups throughout Latin America. PAHO funding helped establish the first influential training program in social medicine at the Autonomous Metropolitan University, Xochimilco, in Mexico City, which attract-ed students from throughout Latin America. Current leaders consistently refer to García’s initiative and tenacity, despite opposition that he increasingly received within PAHO.

In advocating social medicine, García helped distribute Spanish-language translations of works by Vicente Navarro. These works influenced Latin American social medicine with regard to the effects of capitalism, imperialism, and maldistribution of economic resources on health services and outcomes. The International Journal of Health Services, edited by Navarro, provided an English-language forum for Latin American authors.

POLITICAL REPRESSION AND WORK CHALLENGES

Among the 24 in-depth interviews with leaders of social medicine that we conducted, only 4 respondents denied having suffered some form of political repression. Respondents have experienced repression because of their work in Chile’s Unidad Popular government, their activity in human rights, or their role as health care activists. The forms of repression have included torture, imprisonment in concentration camps, exile, exclusion from government jobs, loss of economic security and work stability, loss of professional prestige, and restriction of political activity.

The work process in social medicine varies widely, depending on political and economic conditions. From Chile and Argentina, most leaders of social medicine took refuge in other countries. These refugees from South America’s southern cone made major contributions to the dissemination of social medicine while they were living and working abroad. If people remained within their homelands, they usually supported themselves through clinical laboratory work, market research, or retail sales. Since the fall of the dictatorships, people in social medicine have faced great difficulties in attempts to reintegrate themselves into universities or medical schools. Most hold multiple jobs, usually in clinical or administrative work, and pursue social medicine as largely unpaid activities.

In countries without dictatorships, or where dictatorships proved somewhat less brutal, such as in Brazil, fewer people needed to emigrate and more remained at work in universities or teaching hospitals. In Colombia, owing to a tradition of violence, prominent leaders of social medicine have perished or entered exile despite the presence of elected governments. In other countries such as Mexico, Ecua-dor, and Cuba, participants in social medicine have been able to maintain relatively stable academic positions. Currently, the most favorable institutional conditions for social medicine exist in Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, and Cuba. Although conditions in Argentina, Chile, and Colombia remain more adverse, participants in social medicine struggle to achieve high levels of productivity.

THEORY, METHOD, AND DEBATE

Latin American social medicine has developed into a rich and diverse field rather than a single, homogeneous tradition. Intense debates have focused on theory, method, and strategies for change.53 For instance, theoretic debates have questioned the usefulness of traditional Marxist analysis as opposed to more recent theories. Theoretic differences also have focused on the primacy of economic forces vs other issues such as gender and race/ethnicity. Methodological debates have considered the balance between quantitative and qualitative methodologies in research, as well as individuals vs groups as units of analysis. Strategically, practitioners of social medicine have differed widely in their willingness to collaborate with international health organizations and multilateral lending agencies.

If there is one commonality that distinguishes the field, however, it is an emphasis on theory. Practitioners of social medicine have argued that a lack of explicitly stated theory in North American medicine and public health does not signify an absence of theory. Instead, an atheoretic or antitheoretic stance means that the underlying theory remains implicit. Latin American critics have used this prism to interpret the North American tendency to focus on the biological rather than social components of such problems as cancer, hypertension, and occupational illnesses. The biological focus, from this perspective, reduces the unit of analysis to the individual and thus obscures social causes amenable to societal-level interventions.27,54

Referring to the linkage between theory and practice, practitioners of social medicine frequently use the term “praxis.” Influenced by Gramsci’s work in Italy, Latin American leaders have emphasized theory that both informs and takes inspiration from efforts toward social change.45,55 Research and teaching activities often take place in collaboration with labor unions, women’s groups, Native American coalitions, and community organizations.56

If there is one commonality that distinguishes the field 94. Stolkiner A. Tiempos “posmodernos”: ajuste y salud mental. In: Cohen H, de Santos B, Fiasché A, et al. Políticas en Salud Mental. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Lugar Editorial; 1994:25�53.